By Luqman Abdur-Rahman

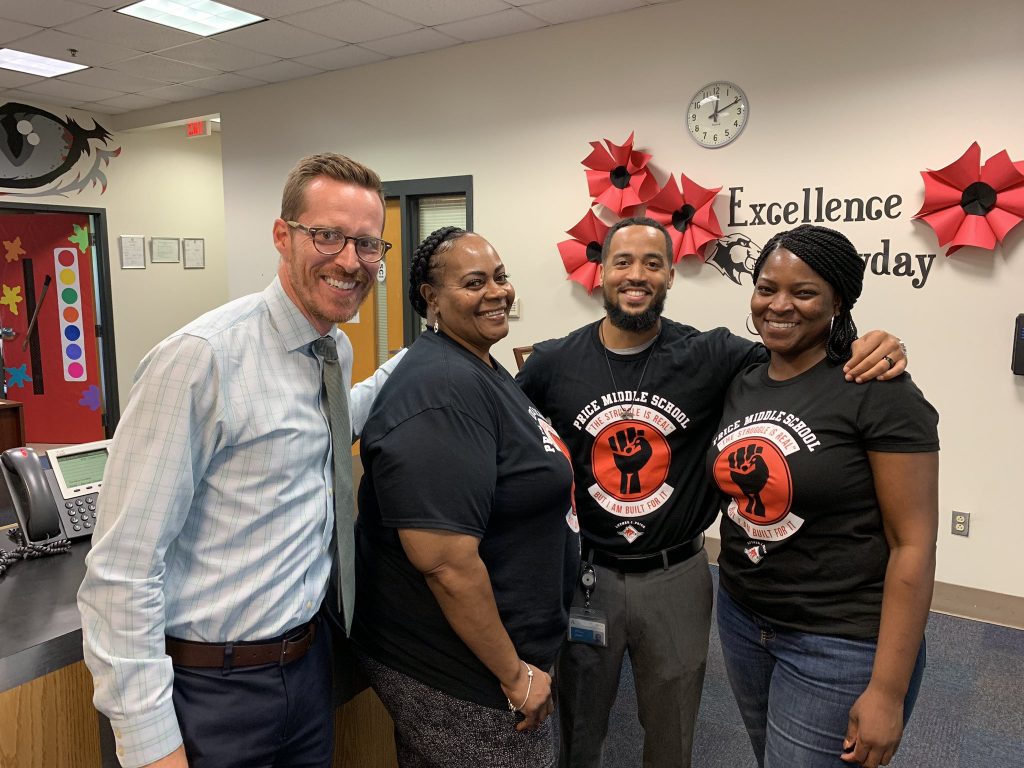

Price Middle School Principal

There is a quote by Lerone Bennet that reads, “An educator in a system of oppression is a revolutionary or an oppressor.” It always seemed like a harsh generalization to me.

It places myself and my well-intended and hardworking colleagues into well-defined camps of either doing the divine work of liberating the minds of the next generation (and hence possessing the key to the lock on the cover of Carter G. Woodson’s “Miseducation of the Negro”) or being complicit in the seemingly endless quest to keep a sleeping giant comfortable in its slumber.

The quote begs the ultimate question of whether or not we, like the statue of the great educator Booker T. Washington at Tuskegee and at Washington High School, seek to remove the veil from over the eyes of the slave, or place it more firmly over his head (referenced masterfully in the Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison). After innumerous hours of self-reflection and study, I have concluded that this quote by Bennet could not be more true, but the reasoning for me is a new revelation.

I thoroughly enjoy my work as principal of Price Middle School and Purpose Built Schools in the Carver cluster of Atlanta Public Schools. It is the hardest work I have done, so I always want to acknowledge my admiration of those I fight alongside daily to create a better future for our babies, who are so deserving. My respect for my peers at Price and across the cluster is eclipsed only by my unconditional love for the children, who are my children.

They are the sun and the moon, tenacious in their desire to learn despite some of the worst imaginable circumstances, and unyielding in their stubborn refusal to accept anything less than the respect they are due. Some of them rebel against the structure they love and need, and others deflect from the recognition of a gap in their learning.

However, this behavior, coupled with some serious intermittent impulsivity, is indicative of our student’s strength and unlimited potential, not a fatal flaw or affirmation of their ineptness. This behavior is analogous to freshly permed hair that takes “one drop” of rain to curl right back up into that tight loop, reminding us that the same stubborn strength that frustrates us also allows us to take whatever shape we must to survive.

I have found that what makes us, as educators, the same as our students is that we have the same enemy. It is a lack of self-efficacy in the educational context – in other words, we are not always confident that we have full control over executing what it takes to produce the academic results we desire. In short, we do not believe we can do it.

I often wrestle with the question of whether I am more frustrated by the fixed mindset that hinders my students or the fixed mindset that sometimes cripples us as a staff. Both groups know that we are brilliant. Our ancestors show it. The footnotes of the history book show it (if you know where to look). Our intuition knows it. But we struggle to reconcile years of academic failure on statewide assessments in our cluster and an inability to break the cycles of fear, poverty, and trauma in our schools and even in our own lives. We know how hard we work every day and throughout a long school year, and it is deflating to not see that GMAS and CCRPI bar graph leaping up, which for many would justify the huge sacrifice we are asked to constantly make.

Our biggest problem as educators is that we believe the image staring back at us in the cracked mirror. We operate within a larger context of intense oppression in our city and our nation. We live in a city with the black mecca of higher education and symbols of black success everywhere, yet we have less social mobility than any other city in the country. This paradox is paralyzing.

The adults working in challenging urban schools like ours boomerang deflection about our inability to overcome this gripping larger educational context by blaming children, blaming parents, and blaming each other. We fight change in our schools and new initiatives like intense data analysis because we tried our best in the last one hundred initiatives and it did not free us from the perils of urban education and seemingly perpetual failure. It is the ultimate reminder of our lack of self-efficacy at what we desire most.

Our students end up fighting those that love them to protect the dignity they need to persist another day. Their rebellion is ours. As teachers, (and holder of the knowledge in a banking system of education) we represent a reminder to our babies that they cannot succeed at this “school thing,” even though they know in their hearts and souls that they are geniuses. Our frustration with the manifestation of their trauma is a tacit admission that we do not think we can free them because we have yet to overcome our own personal demons. We see our younger selves in them, and we relive our darkest moments of insecurity and self-doubt. We sometimes distance ourselves from the students most like us because we cannot relive these times. We doubt if we are equipped to liberate our students because we have yet to figure out how to liberate ourselves.

Our lowered expectations transform us into oppressors in another right. We stop demanding excellence from ourselves and our students. We let things slide during transitions. We allow students to act like they do not care about their grades. We do not address the cell phone under the desk. We accept eighty percent of our class being on task. We water down our assessment so our students – and subsequently we as educators – feel a little bit of the success we desperately desire. We further sedate the sleeping giant. We succumb to a belief that we should at least make the slumber more comfortable.

The only escape from this vicious cycle is revolution.

A revolution does not have to be a grand departure. Revolution begins and lives in our minds, our behaviors, and our habits.

It is revolutionary to believe, without a shadow of a doubt, that our students are as capable as any in this city, country or world. We have confidence that any of our students, with access to the love and knowledge we provide, can break the cycle of generational poverty if they work hard.

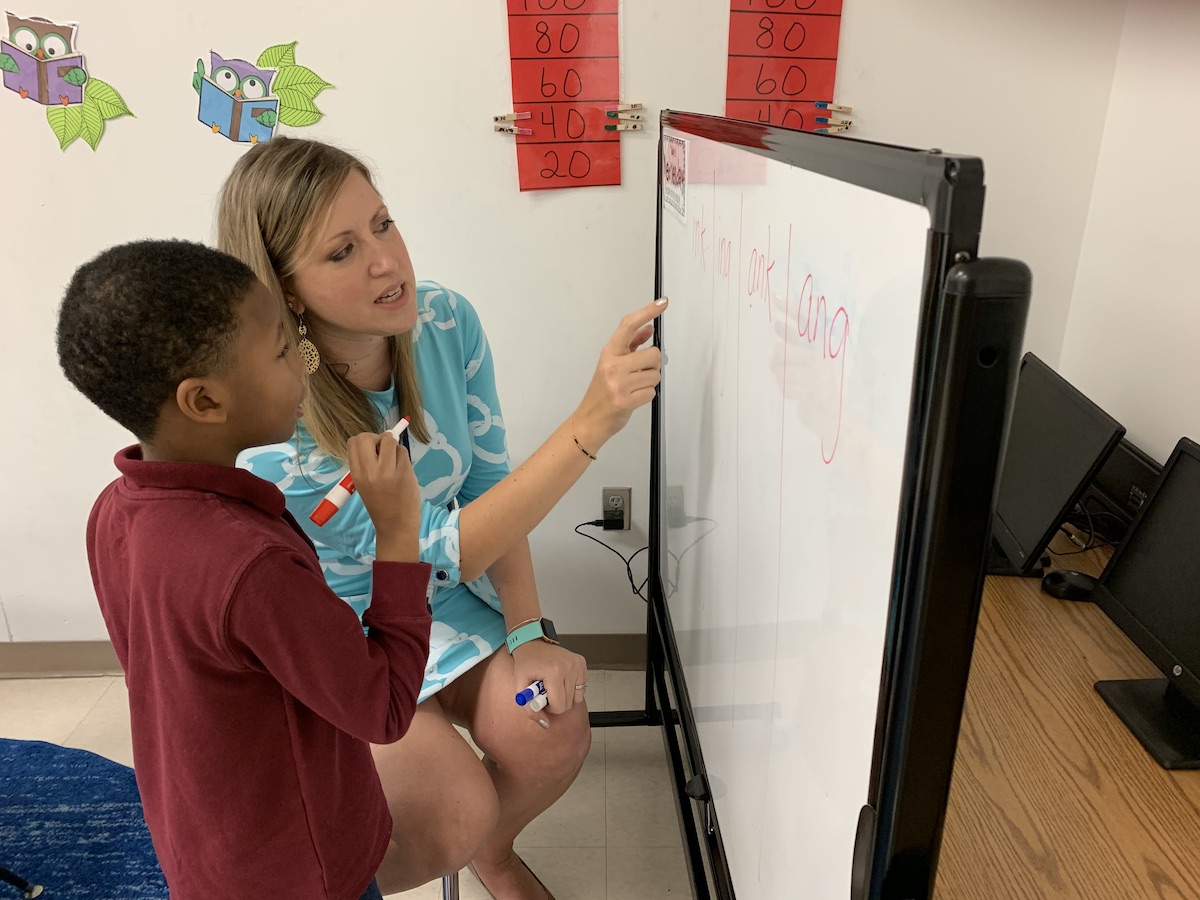

Revolution is full belief that our minds contain the project-based learning driving question that will unlock engagement for our students and show them why the standards we are charged to teach really do relate to their everyday lives.

In a larger societal system of self-hate, the ultimate revolution is unconditional love for ourselves and our students.

It is hard to imagine how wildly rebellious the refrain “black is beautiful” was in the 1960s when every image in society said otherwise. It is difficult to imagine how crazy it was for Harriet Tubman to say “we out” (admittedly, I am paraphrasing), asking us to leave the bondage that represented all we knew at the time. This type of revolution is the type that burns inside us and will lead us to the next stage of liberation for our communities.

Our next revolution starts and ends with us. We live in the time of a need for a “black is brilliant” revolution. We have to wear our brilliance like a crown. We have to see our babies as the software engineers, holistic doctors and practitioners, community leaders, and attorneys who will not only have a choice-filled life, but who will disrupt these larger systems of inequity and oppression.

Our next revolution starts and ends with us. We live in the time of a need for a “black is brilliant” revolution. We have to wear our brilliance like a crown. We have to see our babies as the software engineers, holistic doctors and practitioners, community leaders, and attorneys who will not only have a choice-filled life, but who will disrupt these larger systems of inequity and oppression.

But before we see that, we have to look in that cracked mirror and see ourselves as the vehicles through which this transformation happens.

We have to be the conductors. We have to love and teach without fear and without apology. We have to heal ourselves and one another simultaneously.

For me, this looks like laughter. It looks like keeping your inner child healthy. It looks like meditating and connecting with students in homeroom. It is working out on Tuesday and Thursday with our crew. It is traveling with family during our breaks. It looks like starting each day anew.

I encourage you to heal and “find your beach.” I, for one, remain hopeful, optimistic and eager to work like my life depends on it, because it does. I believe black is brilliant because I am, and if I do not provide this mirror image of unyielding and undying self-belief for my students than no one will.

So I ask my comrades at Purpose Built Schools to rise up and free themselves. Practice habits of self-care and focus on the miracles that happen in our classrooms daily.

Reward children for their great work. Celebrate our teammates and the sacrifices they make every day. Acknowledge their amazing work, and challenge them to do better. Put more attention on the great things and seek new ways to conquer the challenges the classroom provides. Look at your students and see your children.

Then, work with those same stakes in mind. Our work is hard, but someone in our cluster is a master at the very instructional or administrative skill that eludes you. Seek it like the last piece of that one-thousand-piece puzzle. Choose your side in this educational continuum.

Be a revolutionary.You deserve the benefits that come with this decision just as much as our children do.